The Black Lives Matter movement has seen large-scale protests and gatherings take place around the world, highlighting racial injustices and police violence against specific communities. Back in London in the latter half of the 1970s, a similar grass-roots protest movement gathered pace, using music to oppose the rise in racism and far-right organisations like the National Front.

Rock Against Racism was led by Jo Wreford, Roger Huddle, Pete Bruno, Red Saunders and Yorkshire-born Syd Shelton, who were initially galvanised into action by racist comments made on stage by the high-profile rock star, Eric Clapton. They began organising gigs, committed to showcasing multi-cultural Britain and music including reggae, soul, rock’n’roll, jazz, funk and punk. The RAR founders promoted the events through a popular zine named Temporary Hoarding, which Shelton helped design and populate with photographs.

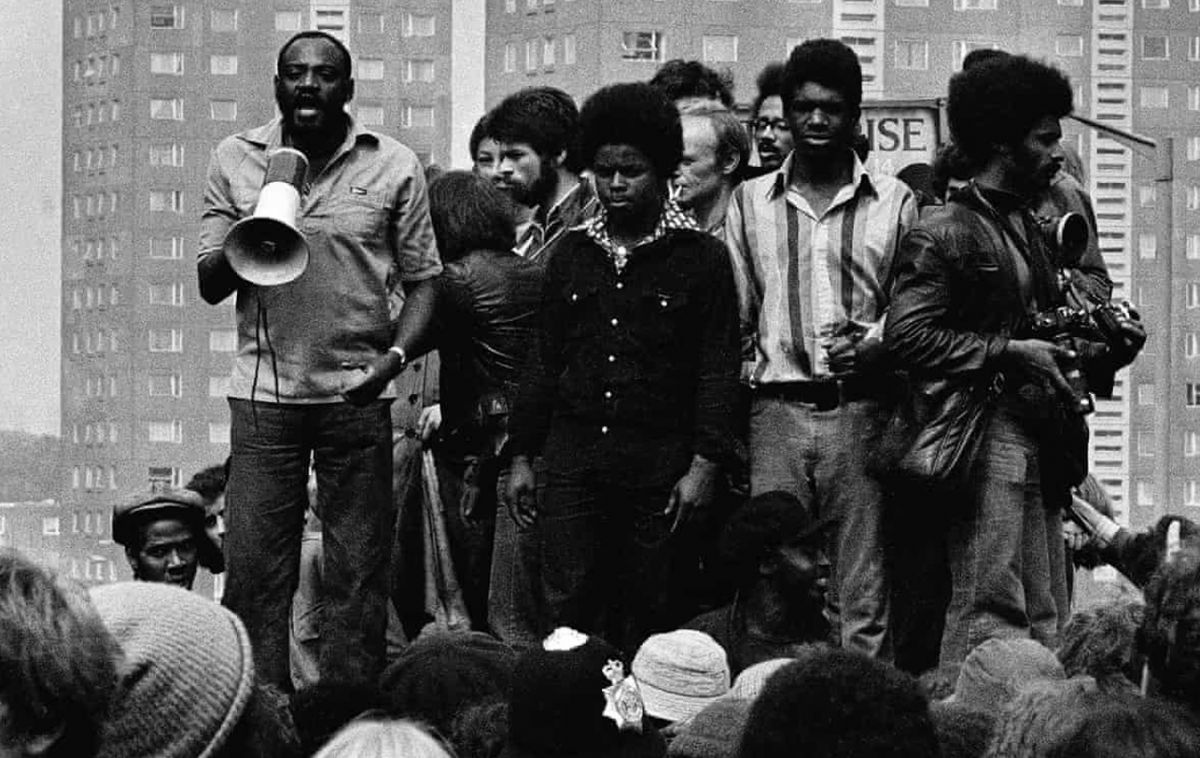

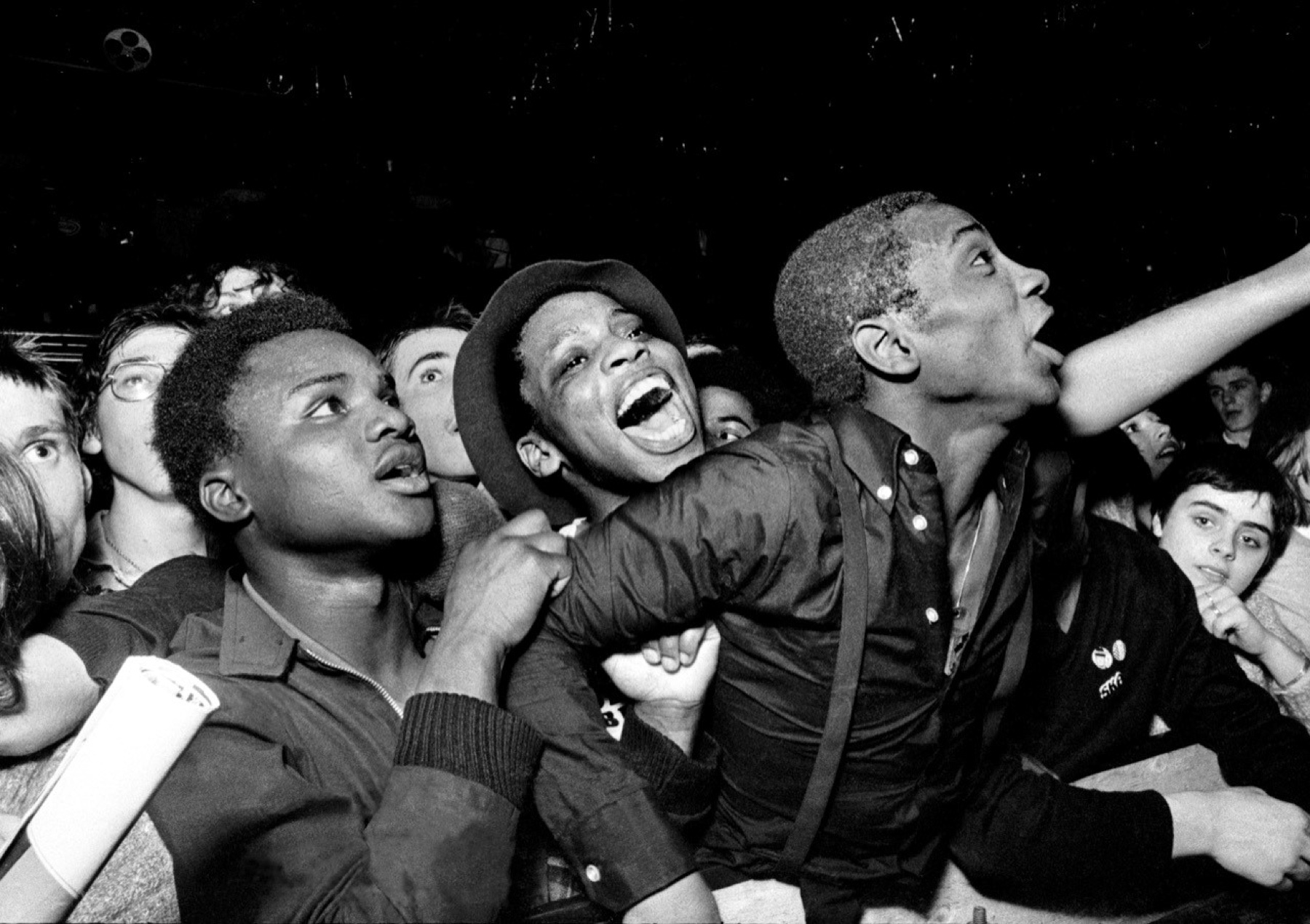

By 1978, one of the biggest and most iconic of the Rock Against Racism outdoor concerts took place in Victoria Park, East London, organised in conjunction with the Anti-Nazi League. Attended by 100,000 people from all over the country, artists appearing that day included punk and reggae pioneers The Clash, Steel Pulse, Misty in Roots, X-Ray Spex and the Tom Robinson Band.

Shelton’s remarkable archive of photography from the era captures the crowds and performers at the thrill-packed atmosphere of RAR’s larger gatherings. In tandem, he photographed diverse subculture portraits on the streets of East London and beyond.

A selection of his archive photography and original Temporary Hoarding graphics were first published in Shelton’s Rock Against Racism book in 2016, while this September 2022 sees the launch of a significantly updated second edition of the book.

Here, the legendary lensman recalls the tumultuous and celebratory times of Rock Against Racism.